Introduction to Pathology

The word pathology originates from the Greek words Pathos (suffering) and logos (study) and as its name implies it is a discipline devoted to the study of the cause, the pathogenesis, the morphological changes and functional derangement in cells, tissues and organs that underlie disease.

With the advent of new technologies, pathologists are able to make diagnoses by examining a whole organ, a fragment of tissue, or even a few cells.

They integrate data from gross and microscopic examination, cytological and molecular methods so that they can face common diseases such as cancer and inflammation. In order to face the challenges in the modern era, a pathologist needs solid basic training and continuous up-dating of modern techniques and novel disease entities throughout a working lifetime.

Branches of Pathology

Diagnostic pathology has many sub-specialty fields. Some are determined by the age of the patients, such as paediatric pathology. Others are related to the type of sample received, such as cytopathology. Some are related to the methods of analysis, such as molecular pathology.

Most sub specialties, however, are according to organ systems, such as gastrointestinal pathology, liver pathology, gynaecological pathology or neuropathology. In community hospitals pathologists tend to practice in all subspecialty areas, but seek expert opinions in case of doubt. In large teaching hospitals or University hospitals pathologists tend to specialise and dedicate their professional activities to one (or a few) specific areas.

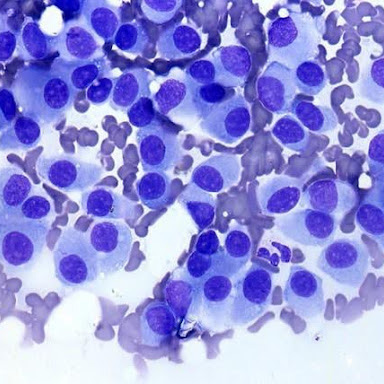

Cytopathology includes both diagnostic and screening components. Diagnostic cytology uses non-invasive and minimally invasive techniques to collect cellular material to confirm or exclude malignancy. Specimens examined include sputum, urine, brushings and washings from various organ systems and fine needle aspirates of palpable or radiologically identified lesions. Cervical Screening Programmes rely upon the Liquid Based Cytology (LBC) in order to identify premalignant disease in asymptomatic women.

Histopathology is the branch of pathology that deals with the tissue diagnosis of disease. The tissue on which the diagnosis is made is biopsy material taken from a patient to detect and diagnose disease, examine disease progression including the response to treatment or lack of response, and to establish the cause in cases of sudden or unexpected death.

A large part of this is the detection and diagnosis of cancer. A tissue diagnosis is essential before starting treatment involving major surgery, radiation or drugs, treatments which may have major side-effects.

History of Pathology

The earliest beginnings of pathology are traced to ancient Egypt, Rome, and Greece. Celsus, a Roman, noted the clinical features of what is now known as “inflammation.”

Galen, another Roman, was an authority on anatomy and other medical subjects; his teaching went unevaluated until 1,300 years later. The first physician known to have made postmortem dissections was the Arabian physician Avenzoar (1091–1161).

In the Renaissance, many artists and scholars advanced the study of anatomy and pathology. Of these Vesalius, the famous anatomist who wrote “De Fabrica Corpora Humani” and Benivieni, a physician who conducted the first autopsy, stand out.

As autopsies, initially prohibited for religious reasons, became more accepted in the late Middle Ages, people learned more about the causes of death. In 1761 Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682 – 1771) published the first book to locate disease in individual organs. In the mid-19th century the humoral theories of infection were replaced first by cell-based theories (Rudolf Virchow), further refined by the development of bacteriology by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur.

When the microscope was focused on samples of diseased cells and tissues, pathology came to resemble what it is today. Rudolph Virchow, who was very instrumental in the early development of diagnostic pathology, incorporated his life-long study of microscopic pathology in his book, “Zellular Pathologie’.

With the light microscope it became possible to correlate the observed signs and symptoms in an individual with cellular changes. In its early stages pathology was very descriptive. Diseases were categorized by how gross and microscopic anatomy was altered.

In the last half of the 19th century, by using this approach to pathology, coupled with microbiological techniques, it was learned that the major causes of human death were biological agents: protozoa, bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Infectious diseases took a heavy toll in human lives. Better sanitation and public health measures were instrumental in controlling these diseases, and the introduction of antibiotics and immunization procedures further reduced their importance.

It is now apparent that all diseases reflect changes at the molecular level. As a consequence, studying cells and molecules involved in disease processes has become the cornerstone of modern pathology. Molecular techniques have also been widely introduced in diagnostic practice. Proteins can be detected in cells and tissues through a technique called immunohistochemistry. A wide variety of sophisticated methods is now available to study the involvement of genes in disease.

Pathology is both an old and very modern medical discipline that is and will remain at the centre of diagnostic medicine.

What is pathology?

Pathology is about understanding disease. In this context, the meaning of the term “disease” is ‘any deviation from normal’, slight or serious. Popularly, pathology is called ‘the science behind the cure’.

Pathology is a medical specialty studying disease processes, how they develop and what they are caused by and the application of this knowledge to the diagnosis of disease. Pathology is considered part of laboratory medicine, a group of medical specialties that study body fluids, such as blood and urine, and cells or tissues to diagnose specific diseases and thus assist medical practitioners in identifying the cause and severity of disease, and in monitoring treatment.

In Europe pathology is synonymous with histo-and cytopathology, that part of laboratory medicine that uses tissues (histopathology) and cells (cytopathology) to make diagnoses. In addition pathologists perform what can be called ‘the last medical consultation’, the post-mortem examination or autopsy.

In North America and the United Kingdom medical specialists that contribute to the diagnosis of disease by measuring substances such as proteins and salts in blood, sputum, bone marrow, and urine are called chemical pathologists.

Modern medicine relies on the combined medical and scientific skills of pathologists to assist in the investigation and management of a patient’s illness.

At the heart of pathology is the care of the patient. The pathologist must produce accurate and reliable diagnoses quickly in response to his/her colleagues’ requests. The pathologist in turn relies on a modern pathology laboratory that offers a wide spectrum of technologies that assist in extracting detailed information from the cells and the tissues. The pathology laboratory is a complex operation that relies on the skills and teamwork of many people to ensure that each patient and doctor receives the best service possible.

Who is the pathologist?

A short way to put it is that the pathologist is “the doctor’s doctor.” Pathologists do not regularly see patients but are, in effect, consultants to physicians from other disciplines in providing detailed diagnoses.

Pathologists are medical doctors who take at least four years of training after medical school in order to become familiar with all aspects of using cells and tissues, interpret microscopic images and the results of molecular tests, make detailed and accurate diagnoses, predict the outcome of disease, and, more recently, determine how patients will respond to special forms of treatment. Although pathologists have limited direct patient contact, they are essential members of the patient’s primary health care team.

The modern pathology laboratory requires the skills of highly trained professional scientists and technicians, to ensure that a maximum of relevant information is extracted from the often very small cell or tissue samples and that the investigations are performed efficiently and accurately.

Specimens can be body fluids, such as blood or urine, from which cells are extracted which can then be further analysed in detail. Specimens can be cells taken from body surfaces such as the cervix of the uterus to make preparations for the diagnosis of human papillomavirus infection or cervical precancer.

Specimens can be small tissue samples taken at endoscopy or by sampling an organ with a needle. Specimens can also be organs or parts of organs resected by the surgeon, or a whole body, in case of an autopsy.

Once the specimen has arrived in the laboratory, depending on the tests requested, various expert departments may be involved in the investigation. Some tests are simple and can be performed rapidly, though more complex tests can take days. Some tests can only be performed by highly specialised laboratories.

Future of Pathology

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, the ESP organized a symposium on the ‘Future of Pathology’.

This festive assembly of key people from the past and present ESP stimulated reflection and discussion as to where Pathology stands, where it is going in the 21st century and which role ESP can and should play in the evolution of this central discipline of modern medicine, to further understanding of disease and for the benefit of our patients.

The presentations given during this symposium are freely available here.